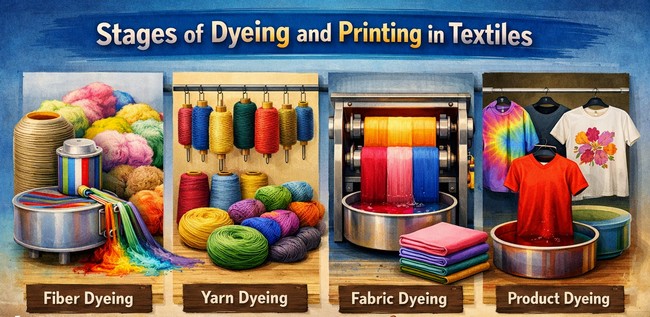

Stages of Dyeing and Printing

The stage at which color is applied has little to do with color fastness but has a great deal to do with dye penetration and shade depth. Dye stage is governed by fabric design, quality level, and cost and end-use requirements. Color may be added to textiles during the fiber, yarn, fabric, or product stage, for desired color effects, depending on the color effects desired and on the quality or end use of the fabric. Better dye penetration is achieved with fiber-dyeing than with yarn dyeing, with yarn dyeing than with piece-dyeing, and with piece-dyeing than with product-dyeing, maximum to minimum. Good dye penetration is easier to achieve in products in which the dyeing liquid or liquor is free to move between adjacent fibers, ensuring liquor circulation. This freedom of movement is easiest to achieve in loose fibers with minimal packing density. It is more difficult to achieve in products in which yarn twist, fabric structure, and seams or other product features minimize liquor movement and cause liquor flow restriction. Because pigments are bonded to the surface, the stage at which printing is done is more related to the desired look, surface-color effects, end use, or product type.

Manufacturers and producers want to add color to products as late in processing as possible because it enables them to respond quickly to demand for fashion colors and quick style changes. But this puts tremendous demands on dyeing and precision process control. It is absolutely essential for goods to be prepared well with thorough pre-treatment in order for good dyeing to occur. The earlier color is added in processing, the less critical is the uniformity or levelness of the dyeing, allowing shade consistency tolerance. In fiber dyeing, two adjacent fibers need not be exactly the same color since minor color differences in the yarn will be masked because of the small surface area of each fiber that is visible, creating visual blending effects. However, the color must be level in products that are sewn before the color is added for uniform garment appearance. Areas along seams where the color is slightly irregular will be obvious and will result in an item being labeled a second through quality control rejection and a financial loss for the producer. Level commercial dyeing is not easy, as anyone who has attempted dyeing on a small scale can attest to process-sensitive work.

Printing also demands uniform and level color for the same reasons and consistent visual impact. Areas along seams that differ in color intensity in prints create the same kinds of problems as for dyed textiles, like seam shade mismatch. In this article I also discuss the stages at which the dye or pigment is added to the textile as color application timing. Dyeing can be done at any stage from fiber onward. Printing is almost always done at the fabric or product stage, but some yarns are printed using limited yarn printing. Product printing usually means that a design is applied to one or more areas of the product, such as the designs on the fronts or sleeves of active sportswear as localized garment decoration.

Fiber Stage

In the fiber-dyeing process, color is added to fibers by pre-spinning coloration before yarn spinning. Many fiber-dyed items have a slightly irregular color, like a heather or tone-on-tone gray with subtle mottled appearance. Printing of fibers does not occur because the same effect can be achieved using less labor or equipment intensive processes through more economical methods.

Mass pigmentation is also known as solution-dyed, producer-colored, spun-dyed, dope dyeing, or mass coloration in synthetic fiber coloration. It consists of adding colored pigments or dyes to the spinning solution before the fiber is formed, a color-in-dope technique. Thus, when each fiber is spun, it is colored as an intrinsically colored fiber. The color is an integral part of the fiber and fast to most color degradants, giving excellent colorfastness properties. This method is preferred for fibers that are difficult to dye by other methods, for certain products, or where it is difficult to get a certain depth of shade, showing solution-dyeing advantages. Colors are generally few because of inventory limitations and limited shade range. Examples of mass-pigmented fibers include many olefins, black polyester, and acrylics for awnings and tarpaulins in outdoor performance applications.

Another type of dyeing similar to mass pigmentation is gel dyeing, an acrylic fiber technique. The color is added to the acrylic fiber while it is in the soft gel stage—the limited time between fiber extrusion and fiber coagulation—as early-stage coloration.

Stock, or fiber, dyeing is used when mottled or heather effects are desired, such as with tweed or heather, for aesthetic variation. Dye is added to loose, staple fibers before yarn spinning as bulk fiber processing. Good dye penetration is obtained, but it is expensive with high processing cost. Top dyeing gives results similar to stock dyeing and is more commonly used in wool worsted systems. Tops, the loose ropes of wool from combing, are wound into balls, placed on perforated spindles, and enclosed in a tank for package circulation. The dye is pumped back and forth through the wool for for thorough saturation. Continuous processes with loose fiber and wool tops use a pad-steam technique for industrial large-scale operation.

Yarn Stage

Yarn dyeing can be done with the yarn in skeins, called skein dyeing; with the yarns wrapped on cones or packages, called package dyeing; or with the yarn wound on warp beams, called beam dyeing—various yarn configurations. Yarn dyeing is less costly than fiber dyeing but more costly than fabric or product dyeing and printing, a mid-range process expense. Yarn-dyed designs are more limited and larger inventories are involved, giving constrained pattern flexibility.

Yarn-dyed fabrics are more expensive to produce because larger inventories of yarns, in a variety of colors, are required and more time is needed to thread the loom or set up the knitting machine correctly, causing higher production complexity. In addition, whenever the pattern of color is changed, time is needed to rethread the loom or change the setup for the knitting machine, leading to time-consuming style changes. Yarn-dyed fabrics are considered to be better-quality fabrics, but it is rare to find solid-color yarn-dyed fabrics, which are mainly patterned goods. It is much cheaper to produce solid-color fabrics by other processes, typically typically piece dyeing. Yarn-dyed fabrics include stripes, plaids, checks, and other structural design or fancy patterns that result from yarns of different colors in different areas of the fabric, giving woven design effects. Examples of yarn-dyed fabrics include gingham, chambray, and many woven or knit fancy or patterned fabrics as classic apparel textiles. Fancy two- or more-ply yarns with each ply a different color are usually yarn dyed for novelty effects.

Printing of yarn is not common, but it is done for specialty fabrics and some yarn used by fiber artists and hobbyists as niche decorative techniques. Warp print fabrics are made from yarn that was printed with a design before weaving, using pre-patterned warp yarns. Some hand knit argyle is made from hand-printed or hand-painted yarn with traditional craft methods.

Piece or Fabric Stage

When a bolt or roll of fabric is dyed, the process is referred to as piece dyeing, a fabric-stage coloration. Piece dyeing usually produces solid-color fabrics with uniform overall shade. It generally costs less to dye fabric than to dye loose fibers or yarns, giving economical bulk processing. With piece dyeing, color decisions can be delayed so that quick adjustments to fashion trends are possible, providing enhanced market responsiveness. Solid-color piece-dyed fabrics of one fiber are common, but piece dyeing offers additional possibilities for dyeing multiple color patterns into a fabric, for complex effects. Yarn incorporating plies of different fiber types or fabrics incorporating yarns representing two or more fibers of different dye affinities or dye-resisting capabilities present interesting possibilities for cross/union possibilities. Cross dyeing is the use of different dye classes in different colors to provide many color combinations and pattern options with simulated yarn-dyed appearance. Union dyeing is just the opposite, aiming uniform shade. Here, the goal is for a solid color even though different fibers are combined or blended in the fabric so that blends dyed evenly.

Cross dyeing is piece dyeing of fabrics, and sometimes yarns, made of fibers from different generic groups—such as protein and cellulose—or by combining acid-dyeable and basic-dyeable fibers of the same generic group, using differential dye affinity. Each fiber type or modification bonds with a different dye class through selective dye uptake. When different colors are used for each dye class, the dyed fabric has a yarn-dyed appearance with multi-hued visual effect. Some products are also cross-dyed, but successful outcomes require well-prepared goods and careful attention to detail and critical process control.

Union dyeing is another type of piece dyeing of fabrics made with fibers from different groups, producing blended-fiber solids. Unlike cross dyeing, union dyeing produces a finished fabric in a solid color with no visible mixture. Dyes that produce the same hue on the fiber, but of a type suited to each fiber to be dyed, are mixed together in the same dye bath as matched dye systems. Union dyeing is common—witness all the solid-color blend fabrics on the market, widely used commercially. A problem with these fabrics involves the different fastness characteristics of each dye class, causing uneven fading tendencies. Aged, union-dyed fabrics may look like a heather because of the differences in colorfastness of the dyes, giving unintentional heather effect.

Product Stage

After the fabric is cut and sewn into a finished product, it can be product- or garment-dyed, a post-construction coloration. Once the color need has been determined, the product is dyed as demand-driven coloration. Properly prepared gray goods are critical to good product dyeing and must be scoured and bleached. Great care must be taken in handling the materials and in dyeing to produce a level, uniform color throughout the product and avoid patchy shading. Careful selection of components is required, or buttons, thread, and trim may be a different color because of differences in dye absorption between the various product parts, causing component compatibility issues. Product dyeing is important in the apparel and interiors industries, with an emphasis on quick response to retail and consumer demands using just-in-time coloration.

Unlike dyeing, printing is mainly done at the fabric stage, but design preparation is a major part of the process. Printing of products is common, especially with items for special events and athletic teams featuring logos and motifs. The print methods most often used include flat screen, heat transfer, or digital as popular industrial techniques. Design preparation, fabric preparation, printing process, fixation, washing and finishing are the major stages in printing process in textiles.

Conclusion

The stages of dyeing and printing in textiles are carefully chosen steps, not shortcuts. Choosing the right stage for dyeing or printing depends on the desired effect, cost, and production timeline. Each stage, from fiber to finished garment, serves a specific technical and commercial purpose.